It’s nearly impossible to remember, for most of us, how we presented ourselves and related to each other before social media became ubiquitous. In fact, it’s not at all unusual for people who are disgruntled with or tired of social media to vent their displeasure on social media. If our kid wins an award or our pet does something cute, if we sustain a grotesque foot injury while touring a Scottish castle, if we see a cloud formation that resembles LeBron James, if we think a political summit went well or badly, or if we’re thrilled to be eating a crab po’ boy in the Denver airport, we can do something about it.

How we handle grief in the age of social media has become an especially visible manifestation of the changed landscape. Just this week I have already seen friends on Facebook mourn the loss of a spouse, a pet, a bid for political office, and a job. Other causes of grief include broken marriages or other relationships, the defeat of causes we believe in, missed opportunities, and even losses in sporting events that have deep significance for us. I’m sure our readers can think of others.

For intensity and duration of grief, nothing compares with the death of someone we love or admire. The deceased may be a family member or friend, or a public figure revered by the bereaved, but in all cases the survivors must deal with some combination of the finality of the loss, the hole left in their lives by the departure of the deceased, the need to pay tribute, the regret associated with things left unsaid or undone, and the need somehow to move on.

And unfortunately, there are those vast collective tragedies–mass shootings, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, etc.–that magnify the grieving experience and add elements of fear, anger, and insistence on a better future. Activist survivors of the Parkland school shooting on February 14 had a dedicated Facebook page up and running by the end of the next day—but one student, Cameron Kasky, was posting on Facebook even before he got home from school on the day of the shooting. His posts led to television appearances and an invitation to write an op-ed for CNN, helping launch a movement that, as The New Yorker points out, “had a name (Never Again), a policy goal (stricter background checks for gun buyers), and a plan for a nationwide protest” within four days of the disaster.

What the Parkland activists did on a large scale demonstrates just how powerful social media has become as a means of addressing tragic circumstances. Businesses, like individuals, have discovered that joining the conversation can be important–but with mixed results. Social media can enable a business to perform good works in trying times, and perhaps improve or reinforce its image, but it also offers unparalleled opportunities for self-inflicted damage. A few simple guidelines are essential:

#1. Offer solidarity without self-promotion.

Companies that don’t actually mobilize people and resources amid tragedy can still play a quiet, constructive, and often-appreciated part in the conversation by offering expressions of sympathy and solidarity in combination with an appropriate visual image. For example, Ralph Lauren opted for a striking Eiffel Tower photo in his social media response to the 2015 Paris terror attacks, and countless businesses used Tricolor themes that together presented a unified front. Support for the cause on social media by so many prominent businesses helped drive an increased awareness and solidarity among members of the general public, who in turn shared their sentiments with friends on social media.

On the other hand, it’s usually a good idea to remain quiet while a tragic event is actually in progress or while very little is known about it. Speaking up too soon looks like an attempt to gain attention, and getting the facts wrong is never good. Certainly, a business should halt all automated posts, which have a way of saying the wrong thing at the wrong time during a crisis.

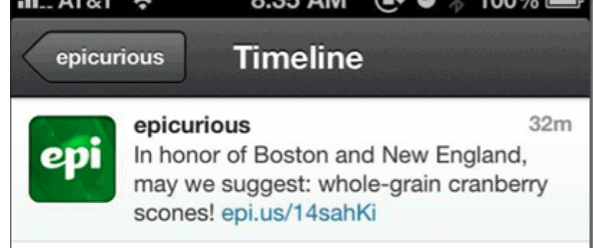

The extreme of unwisdom: In the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing, Epicurious, a food and recipe website, tweeted “In honor of Boston and New England: may we suggest: whole-grain cranberry scones!”

#2. Be of service.

Following the Paris attack, Airbnb opened its doors to provide emergency accommodations, while Google “made international calls to France free via Hangouts.” When Hurricane Harvey struck Houston and surrounding areas, Anheuser-Busch closed one of its breweries and converted to the production of drinking water for the hurricane victims, while Home Depot carried out a pre-existing plan to send tools and supplies to affected areas. Announcing such activities on social media is more of a public service than a self-promotion, provided you don’t actually sing your own praises and you go easy on the logos. You could actually save lives by informing people about your activities. Mobilizing people and services to provide aid, if handled with sensitivity, provides a powerful brand boost, but anything that looks like a brand boost will have the opposite effect. A photo of your product or location is generally going too far.

#3. Keep the spotlight on the cause and the real heroes.

It’s essential for companies performing good works in tragic circumstances to avoid detracting from the stories of the victims and the people performing heroically on the ground. If you are actively involved in providing assistance, you need to establish that you care and that your company is concerning itself with something besides its bottom line while people suffer, but anything that remotely resembles an attempt at the limelight looks insensitive.

In expressing sympathy or solidarity, be sure not to say too much, too often, because that not only deflects attention from what really matters, it also sets you up to look like you regard some tragedies as more important than others if you’re not absolutely consistent about what and how much you say on all such occasions.

And a word to the wise: The death of a celebrity does constitute a tragedy to his or her fans, so it is essential that companies ask themselves whether they belong in that picture. Unless a particular business actually has had some association with the deceased, tributes and accolades have a way of looking like an attempt to poach somebody else’s cool.

No business can afford to be tone-deaf about these matters at a time when social media is increasing the possibilities for people to handle grief more broadly and thoroughly than ever before–and to speak ill of businesses they perceive as having misbehaved. Whether people are too readily offended is immaterial; what matters is that if they are offended at a difficult time, they will blister the guilty party.

Social media has greatly increased the mechanisms available to us during times of turmoil and grief, and as with so many uses of social media, we need good judgment to make a given situation work for us rather than against us. As businesses deciding whether and how to respond to a tragedy, we need to exercise caution about even thinking of a disaster as an opportunity to do anything besides help other people. A well-judged response can be a legitimate means of building goodwill, but the slightest attempt to exploit the situation is almost sure to have the opposite effect.